A Rehearsal for Overcoming AIDS

October 1, 2024

Source: https://caifuhao.eastmoney.com/news/20240925115315100512370?from=guba&name=5YyW5a2m5Yi26I2v5ZCn&gubaurl=aHR0cHM6Ly9ndWJhLmVhc3Rtb25leS5jb20vbGlzdCxiazA0NjUsOTksai5odG1s

295

295

Starting in June 2024, global scholars concerned with HIV prevention will focus their attention on Gilead’s antiviral drug, lenacapavir. At that time, Gilead released the latest data from the PURPOSE 1 trial, which demonstrated that lenacapavir, when administered via two annual injections, resulted in zero infections compared to daily oral PrEP medications. This suggests that, in the absence of successful vaccine development, lenacapavir could potentially serve as a long-lasting preventive alternative. However, whether the results of the PURPOSE 1 trial were a coincidence or a certainty remains unanswered. In September, Gilead further presented results from the PURPOSE 2 trial, indicating a higher likelihood of certainty. The results showed that 99.9% of participants in the lenacapavir group did not contract HIV, representing a 96% reduction in infection risk compared to the placebo group. This might signal that we are approaching an era of highly effective HIV prevention.

01 / The Repeated Failures of Vaccines

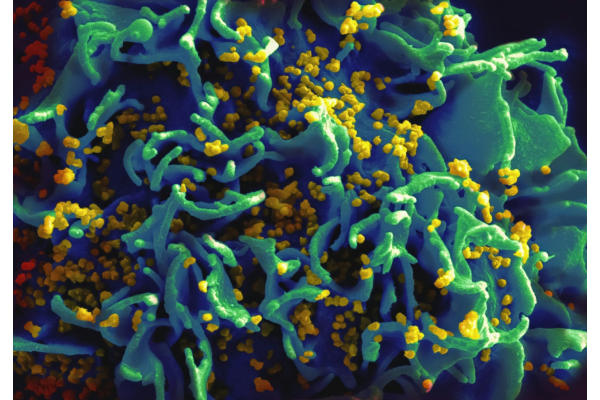

The battle against AIDS dates back to the 1980s. In 1983, two researchers from the United States and France independently isolated the HIV pathogen, introducing the world to this dreadful virus. HIV attacks CD4 immune cells, the commanders of the human immune system. But capture is not enough; HIV uses CD4 cells as its nest to proliferate countless viruses. This eventually leads to a dwindling number of functional CD4 cells, causing the immune system to collapse and rendering the body susceptible to various infections—a minor cold can become fatal for someone with AIDS. Despite a significant understanding of HIV, considerable challenges remain in prevention and treatment: there is still no cure, and a vaccine has yet to emerge.

In 1984, the then U.S. Secretary of Health, Margaret Heckler, optimistically predicted that a vaccine would be available within two years. However, nearly 40 years later, after exploring multiple approaches— from inactivated and live attenuated vaccines to protein subunit, viral vector, and DNA vaccines—tens of billions in research costs, and nearly a hundred vaccine candidates have not met with success. HIV’s primitive and simplistic nature allows for nearly infinite mutation possibilities, presenting overwhelming challenges for vaccine developers. After a major Phase 3 trial failure last January, Johnson & Johnson completely shut down its infectious disease research division, marking another competitive exit from the global fight for an HIV vaccine. This suggests that market entry for HIV vaccine development must be approached with extreme caution.

02 / An Alternative Approach

Clearly, preventing AIDS is not solely reliant on vaccines; antiviral drugs can play a similar role. For over 30 years, oral antiretroviral drugs have been the cornerstone of HIV treatment, greatly improving safety and effectiveness and significantly altering the grim trajectory of early HIV epidemics. Currently, there are clear guidelines for both pre-exposure prevention (PrEP) and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). For HIV-negative individuals, a recommended PEP regimen involves using two or three antiretroviral drugs within 72 hours of exposure for a 28-day course, which can markedly reduce the risk of HIV infection. However, adherence poses a significant challenge for PEP. A meta-analysis showed that as of the end of 2022, overall adherence among healthy patients for PEP was just 58.4%, a mere 1.8% increase since 2014. This indicates that while most individuals consider PEP following exposure, less than 60% actually complete the full treatment regimen. Consequently, the prospect of sustained pre-exposure medication is often unrealistic, complicating AIDS prevention efforts.

The crux of these challenges lies in the requirement for daily medication, which can lead to forgotten doses and subsequent interruptions. Additionally, medication side effects can result in discontinuation. These factors have fueled urgent market demand for longer-acting HIV medications, which positions lenacapavir as a potential solution. With the release of two Phase 3 clinical trial data sets, the potential of lenacapavir is being gradually validated. The PURPOSE 1 trial recruited over 5,300 women in South Africa and Uganda, with the treatment group receiving two lenacapavir injections a year, while the control group took daily oral PrEP medications, Descovy or Truvada. The results showed that zero infections occurred among over 2,000 women in the lenacapavir group, compared to an infection rate of 2.02 cases per 100 person-years in the Descovy group and 1.69 in the Truvada group. This means, with just two injections a year, lenacapavir can lead to zero infections. The PURPOSE 2 trial complemented these findings, involving a more diverse range of subjects from countries including Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, South Africa, Thailand, and the United States, recruiting both male and female participants at risk of HIV. Even though two cases of HIV infection occurred in the lenacapavir group, the overall risk was still 96% lower compared to the control group, underscoring lenacapavir's potential effectiveness.

03 / A Potential “Game-Changer”

"An exciting game changer for HIV prevention." This is how Ethel Weld, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, described lenacapavir following the release of the PURPOSE 2 trial results. Lenacapavir indeed demonstrates high efficacy, lessening the burden of preventive measures over an individual’s lifetime and aligning more closely with other preventive modalities, such as vaccinations. However, whether lenacapavir can truly become a game changer is yet to be determined.

First, its preventive indication will need regulatory approval. According to Gilead, the data from these two trials will support a series of global regulatory submissions, anticipated to begin by the end of 2024, with potential approval around 2025. In addition to successful approval, pricing will be crucial for lenacapavir to become a game-changing option. Currently, the treatment cost for lenacapavir in the United States is $42,000 in the first year and $39,000 each subsequent year, with patent protection lasting nearly two decades. For underdeveloped countries, such high costs are clearly unaffordable. An analysis presented at the 24th International AIDS Conference indicated that the cost of PrEP medication in South Africa needs to drop below $54 per year to be manageable. In comparison, lenacapavir’s competitors, oral PrEP, can cost less than $4 per month due to expired patents. Given this substantial price gap, it remains uncertain whether lenacapavir will reach high-risk populations as intended.

Therefore, international stakeholders urge Gilead to lower lenacapavir's price, ensuring that HIV-infected individuals or those at high risk in low- and middle-income countries can access it simultaneously with wealthier nations, possibly through drug patent-sharing initiatives and allowing the manufacture of generics. A spokesperson for Gilead previously commented that the company’s strategy is to provide high-quality, low-cost lenacapavir to the most needy countries. Perhaps, in the future, we will witness the emergence of a true game changer.

By editorRead more on

- The first subject has been dosed in the Phase I clinical trial of Yuandong Bio’s EP-0210 monoclonal antibody injection. February 10, 2026

- Clinical trial of recombinant herpes zoster ZFA01 adjuvant vaccine (CHO cells) approved February 10, 2026

- Heyu Pharmaceuticals’ FGFR4 inhibitor ipagoglottinib has received Fast Track designation from the FDA for the treatment of advanced HCC patients with FGF19 overexpression who have been treated with ICIs and mTKIs. February 10, 2026

- Sanofi’s “Rilzabrutinib” has been recognized as a Breakthrough Therapy in the United States and an Orphan Drug in Japan, and has applied for marketing approval in China. February 10, 2026

- Domestically developed blockbuster ADC approved for new indication February 10, 2026

your submission has already been received.

OK

Subscribe

Please enter a valid Email address!

Submit

The most relevant industry news & insight will be sent to you every two weeks.