GLP-1 fired a shot at the AD market?

December 11, 2024

Source: drugdu

342

342

As we all know, Alzheimer's disease is still one of the most difficult diseases in the world. The core is that the medical community still knows very little about its pathogenesis. There are currently two mainstream hypotheses about the mechanism of Alzheimer's disease:

As we all know, Alzheimer's disease is still one of the most difficult diseases in the world. The core is that the medical community still knows very little about its pathogenesis. There are currently two mainstream hypotheses about the mechanism of Alzheimer's disease:

One is the Aβ hypothesis, that is, the overexpression of β-amyloid protein (Aβ) aggregates into amyloid plaques; the other is the Tau protein hypothesis, that is, the neurofibrillary tangles formed by the misfolding of Tau protein after excessive phosphorylation.

Regardless of which hypothesis, countless pharmaceutical companies have failed frequently, including the Aβ hypothesis that is most recognized by pharmaceutical companies. According to this hypothesis, the more completely the drug clears the amyloid plaques in the patient's brain, the more beneficial it is for controlling the development of the disease. Donanemab and lecanemab, which have been approved, are the same, but the mechanisms are different.

How much benefit these drugs can bring to patients remains to be answered by time. But in the optimistic scenario, they are successfully approved for marketing, which at least proves that Alzheimer's disease is no longer a "research and development black hole".

As long as pharmaceutical companies can come up with relatively convincing clinical data, regulators do not rule out approving new therapies for marketing. This is undoubtedly a great incentive for latecomers.

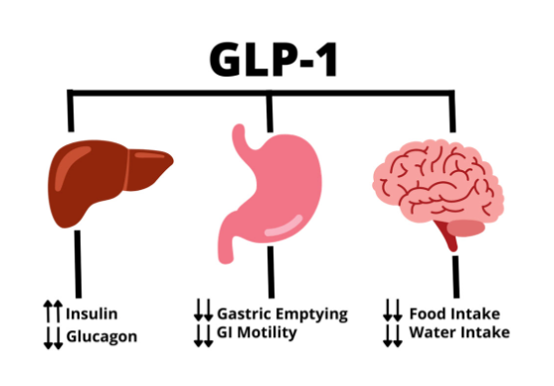

This may also apply to GLP-1. Because GLP-1 treatment of Alzheimer's disease is also based on an unproven mechanism-the inflammation hypothesis.

In September this year, a paper published in Nauter, "Why do obesity drugs seem to treat so many other ailments?", explored the various possible benefits of GLP-1 drugs and the research progress of scientists on the mechanisms behind them. Among them is the inflammation hypothesis.

A clinical study of patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease found that semaglutide can reduce the risk of severe renal complications ( 24%. The study concluded that the kidney protection mechanism was not related to changes in the participants' weight. Instead, the authors hypothesized that the drug worked by reducing inflammation in the kidneys.

Animal studies have shown that drugs that act on GLP-1 receptors can inhibit inflammation in the kidneys, heart, and liver. This actually helps explain why GLP-1 can have a positive effect on MASH.

There are many places in the body where GLP-1 receptors can be found on immune cells, so this is an obvious path. But in some tissues where drugs reduce inflammation, there are almost no GLP-1 receptors around. A study last year found that in these organs, GLP-1 receptors in the brain are likely to be responsible for the anti-inflammatory effect.

The reason for exploring the potential of GLP-1 in Parkinson's and Alzheimer's is also From the perspective of eliminating inflammation. These two diseases have a common feature - neuroinflammation, and current therapies cannot effectively target it.

In both diseases, pathological proteins (β-amyloid in Alzheimer's disease and α-synuclein in Parkinson's disease) interact with certain receptors in the brain to induce inflammation. GLP-1 has shown the ability to reduce brain inflammation and help key biological processes such as the generation of new neurons.

In fact, previous studies have shown a link between insulin resistance and Alzheimer's disease. This hypothesis even led to Alzheimer's disease being called "type 3 diabetes." Several observational studies and meta-analyses have also linked type 2 diabetes to an increased risk of Alzheimer's disease.

Published in the journal Alzheimer's & Dementia in 2022, a retrospective analysis of tens of thousands of type 2 diabetes patients showed that those diabetic patients who had used GLP-1 receptor agonists had a significantly lower incidence of dementia than the control group (HR: 0.47, 95% CI: 0.25-0.86).

If insulin resistance is indeed a factor in Alzheimer's disease, then it certainly makes sense that GLP-1 may help prevent the disease. Of course, this is also unproven.

As early as 2017, Thomas Fortini's team at the Institute of Neurology at University College London found that exenatide could significantly affect the symptoms of Parkinson's patients in actual treatment.

A previous study showed that at 60 weeks, patients treated with exenatide had an improvement of 1.0 points in Parkinson's disease dyskinesia, while patients treated with placebo had a deterioration of 2.1 points. This means The exenatide group performed better in improving Parkinson's disease symptoms.

Sanofi is also advancing the clinical treatment of Parkinson's with lixisenatide, while Novo Nordisk is advancing two global Phase III clinical trials for Alzheimer's disease.

While the market is still waiting for the clinical results of semaglutide, there is increasing evidence of the potential role of GLP-1 in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer's disease.

In October this year, a real-world study published in Alzheimer's and Dementia showed that patients with type 2 diabetes who took semaglutide had a 40% to 70% lower risk of being diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease.

Although the Phase II clinical data of liraglutide for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease released in September did not meet the primary endpoint, that is, there was no significant effect on brain glucose metabolism rate, the study produced signs of efficacy in other indicators.

The data showed that 204 people were randomly assigned to receive placebo or liraglutide at multiple sites in the UK. After one year of treatment, the rate of cognitive decline in the liraglutide cohort was 18% lower than that in the placebo group. And in patients who completed the trial, the changes in cognition were statistically significant.

Patients taking liraglutide had nearly 50% less volume loss in several areas of the brain, including frontal, temporal, temporal and total gray matter, as measured by MRI. Parts of the brain with less volume loss are involved in tasks such as memory, language and decision-making that are affected by Alzheimer's.

Paul Edison, a professor of science at Imperial College London who led the study, said in a statement: "The slowing of brain volume suggests that liraglutide may protect the brain, just as statins protect the heart." Edison pointed out that further research is needed. He said that liraglutide can reduce brain inflammation, reduce insulin resistance, limit the harm of amyloid-β and tau, and improve communication between nerve cells.

Although there is still no clinical registration for tirpotide, the market is waiting to see whether Eli Lilly will join this Alzheimer's treatment revolution.

After all, Alzheimer's disease is another stronghold of Eli Lilly. In July, Donanemab was approved by the FDA for the treatment of adult patients with early Alzheimer's disease. Phase III clinical trials showed that within 18 months, the rate of cognitive and functional decline in early patients slowed by 35%. However, clinical brain edema and a mortality rate of about 0.34% have also made Donanemab's safety questionable.

In contrast, GLP-1 has relatively few side effects, which is an important reason why it is highly expected. Moreover, compared with existing monoclonal antibody drugs, GLP-1 has the advantage of oral administration.

However, there is more and more positive evidence, but GLP-1 still has a long way to go in Alzheimer's disease.

First of all, in terms of mechanism, the reason why GLP-1 treats cardiovascular disease is simple: weight loss almost certainly provides most of the benefits. However, the effects observed in diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and addiction involve other mechanisms, and the mystery of these mechanisms is far from being solved.

At the same time, to treat neurological diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, it is bound to involve the brain and peripheral organs, which requires GLP-1 to have the ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier.

At this point, only animal studies have shown that some GLP-1 drugs can penetrate the blood-brain barrier; it is not clear how deep these drugs actually penetrate into the brain, and some scientists say that these drugs cannot penetrate deeply, only into certain areas where the blood-brain barrier may leak, which may trigger a series of signals from there.

Secondly, safety is also a potential obstacle. Although the side effects of death and brain edema are much lighter than those of AD monoclonal antibodies, GLP-1 is to treat Alzheimer's disease, which means that patients need long-term medication, so it must further prove its long-term safety.

Finally, and most importantly, GLP-1 still needs to be confirmed in clinical practice that it can indeed reduce the incidence or progression of the disease. This requires analyzing a large number of people in randomized controlled trials of patients, and factors such as extremely high costs and clinical management difficulties make this easier said than done.

Fortunately, as early as September next year, semaglutide will read out the phase III clinical data for Alzheimer's disease. According to information disclosed by ClinicalTrials.gov, these two large global multicenter Phase III trials each included approximately 1,840 people and lasted for 173 weeks to evaluate whether daily oral semaglutide (different doses) has a positive effect on early Alzheimer's disease.

As a pioneer, Novo Nordisk's clinical trials may greatly affect GLP-1's enthusiasm for exploring Alzheimer's disease. Previously, some small companies, including Neuraly in the United States and Kariya Pharmaceuticals in Denmark, said they were evaluating the effects of their GLP-1 drugs on Parkinson's disease and considering expanding their research areas to Alzheimer's disease after Novo Nordisk's trials are successful.

More and more evidence cannot change the objective laws, and everything depends on the final clinical data.

It is difficult to make a conclusion until the last moment.

Of course, optimists have made bold predictions that even if semaglutide only shows a small effect in the end, the amyloid hypothesis will be ruined.

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/

By editorRead more on

- 20-Valent Pneumococcal Vaccine Approved for Clinical Trials January 20, 2026

- ADC205 Tablets Received Approval for Drug Clinical Trial January 20, 2026

- Sifang Optoelectronics makes strategic investment in Changhe Biotechnology January 20, 2026

- Mingde Bio plans to acquire a 51% stake in Hunan Lanyi through capital increase and acquisition January 20, 2026

- accelerating the transition of CLL treatment into a “chemotherapy-free era”. January 20, 2026

your submission has already been received.

OK

Subscribe

Please enter a valid Email address!

Submit

The most relevant industry news & insight will be sent to you every two weeks.